Director Anubhav Sinha’s courtroom drama Assi sheds light on the plight of victims, legal lacunae, and public anger against the menace of rape in India.

Rating:

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)

By Mayur Lookhar

Stats don’t lie. As per NCRB’s Crime in India 2023 report, 29,670 rape cases were recorded nationwide – an average of 80 rapes a day and 3.3 per hour. So, a woman is raped every 20 minutes. While 2025 figures await publication, NCRB trend projections estimate 26,337 cases (72 per day). Cops in some areas might celebrate the dip, but consistently over 20,000 annual rape cases should alarm any nation, any society

Filmmaker Anubhav Sinha’s courtroom drama Assi (Eighty) cautions us about the disturbing statistic. Interestingly, as many as nine names appear on its CBFC certificate, implying the film went to a Revising Committee. What were the Examining Committee’s initial concerns? Only director Sinha can answer that, because you won’t get an explanation from CBFC.

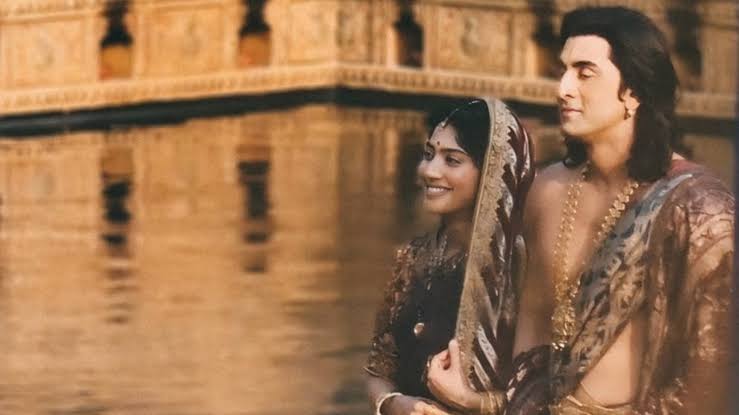

Story

Sinha’s Assi unfolds in Delhi-NCR. Parima (Kani Kusruti), a humble Delhi schoolteacher, attends a colleague’s farewell party. Seeing her dance happily, her husband Vinay (Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub) urges her to stay longer. At 10 pm, she takes the last metro (arriving 10:30 pm), steps out alone, and is abducted and raped by five men in an SUV. Left for dead on a railway track, she’s saved by a Good Samaritan at dawn. Seeking justice isn’t just her husband, advocate Raavi too (Taapsee Pannu) is determined to deliver it. A couple of the accused are influential, making it doubly difficult.

Screenplay and Direction

At 133 minutes, Assi is fairly well written by Gaurav Solanki and Sinha, the duo behind the brilliant Article 15 (2019). The screenplay isn’t as taut as Thappad (2020) or Mulk (2018), nor is the subject novel, but they succeed in sparking the right conversation around this heinous crime. Beginning as a serious courtroom drama, it veers into vigilante territory, where it’s likely to engage audiences most, without losing sight of its pragmatism. It raises the pertinent question: How do we as a society tackle this menace? Should rapists face the law or vigilantes? In a nutshell, Assi sheds light on victims’ plight, legal lacunae, and public anger against the menace of rape in India.

Along the way, Assi takes certain creative liberties most prominently, allowing the victim’s child to be present in court. In the climax, the courtroom fills with schoolchildren. Legally untenable, but we live in times when even infants are raped. Recently, society was shocked when three teens – one aged 10, raped a 6-year-old. This kind of horror numbs you, breaks society’s spirit, and leaves us speechless. Sinha’s Assi stands apart from similar films by showing how rape devastates an entire family. Children’s courtroom presence is symbolic: when even kids aren’t safe, they must see justice in action.

Given the alarming cases, the very sight or mention of the dreaded word breaks you. No sane individual likes seeing a rape scene. While Sinha is a sensitive filmmaker, he errs by stretching the crime scene longer than needed. It’s disturbing and makes you angry, but perhaps it’s done to inevitably justify the subsequent vigilantism.

Performances

She’s been around for ages but has shown only flashes of brilliance. In Thappad, Taapsee Pannu’s defiant attitude worked as she was the victim. In Assi, she could have reined it in a bit, but with the victim traumatized, her lawyer must stay strong. Pannu starts sluggish but shines in the final act, conveying not just the victim’s ordeals, her truth, but a teary-eyed frustration with women’s safety and the tiring judicial system. Sinha’s films seldom rake in moolah at the box office, but Raavi in Assi helps Pannu end her long drought.

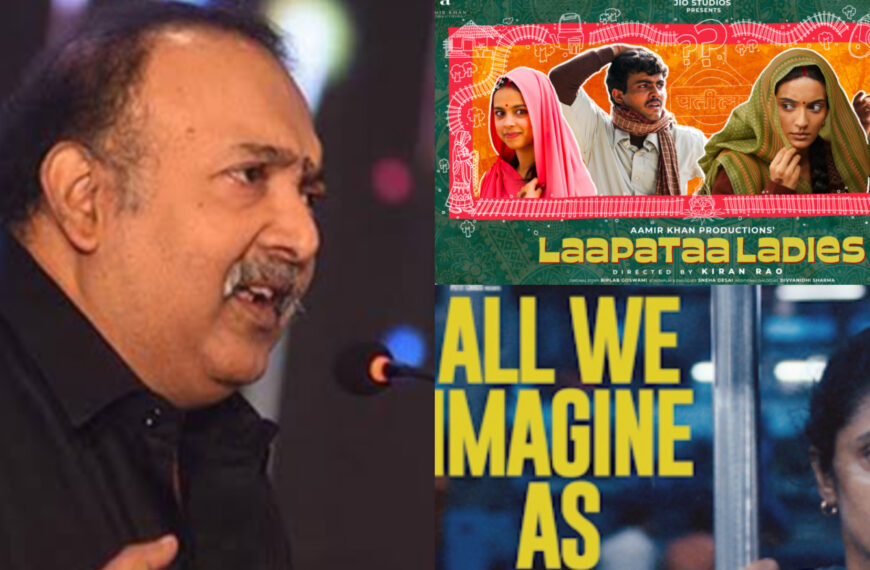

Kani Kusruti has charmed critics with her acclaimed roles in All We Imagine as Light (2024) and Girls Will Be Girls (2024). A Malayali girl raped in Delhi subtly nods to the North-South divide. Before Haryanvi monsters ruined her life, Parima faced personal challenges marrying a North Indian. During a conversation with his mother, Vinay corrects her: his wife isn’t Madrasi but Malayali.

It’s as the rape victim that your heart goes out to Parima. Kusruti finely emotes her mental and physical pain. Often, we lose sight of how traumatized victims are during the crime and later making it hard to recognize rapists. The law and Raavis help seek justice, but a Parima mirrors thousands yearning for it while fearing societal judgment. All they want is normalcy. Here, the teacher is stunned when her ordeal becomes WhatsApp gossip in her students’ group – some kids who she taught. From the rape onward, Parima’s life is dictated by circumstances. Conversations with her husband dwindle; barely any with her son. Rape victims are coached to guard against defense lawyers. After early struggles, Parima drops her veil and speaks her mind, discovering her strength. Kusruti’s sensitive, realistic portrayal captures Parima’s quiet resilience, making her the emotional core of Assi.

Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub’s Vinay is an intriguing character. Most husbands would be filled with rage, thirsting for revenge, but here is a man who, despite the horrific episode, chooses to remain calm. Without saying much, he quietly hopes for justice but doesn’t let this dark chapter break him. With no emotional support, Vinay must stay strong for his wife and only child. He surprises you by telling his son that most people in this world are good, such writing allays stereotypes and fears of North Indians, particularly Haryanvis. Vinay, however, has no answer when his son asks why some are bad. Zeeshan wins you over with a mature, sensitive portrayal.

Kumud Mishra has a remarkable image makeover. Looking much leaner with a new hairdo, his Kartik is an intriguing character – one crucial to the film’s vigilante debate. Naseeruddin Shah’s Basu Sir has no such ambiguity. The vigilante here wears no cape but simply carries an umbrella that serves as a metaphor for delivering justice while protecting against prying eyes.

Manoj Pahwa and his wife Seema Bhargava Pahwa feature in many of Sinha’s films, but the duo is slightly off-colour in Assi. Satyajit Sharma is more than competent as defense lawyer Navratan. Early on, sincerity in Navratan’s eyes makes viewers wonder if this isn’t an open-and-shut case. Revathy’s Justice Vasudha empathizes with the victim’s plight but won’t let it sway her fact-based judgment.

Sinha’s love for Ramdhari Dinkar shines through again, with Jatin Goswami’s investigating officer ASI Sanjay revealed as a fan. Remember how Kumud Mishra’s character was a Dinkar devotee in Thappad. Literature and great poets shape philosophies, but too often, not all have the courage to follow them.

Music / Technical Aspects

A courtroom drama limits outdoor shoots, but Sinha’s resident cinematographer Ewan Mulligan leaves his mark here too. That final shot of the bleeding vigilante collapsing, with kin desperately trying to save him, and Sinha and Mulligan tilting the camera as if viewed through the vigilante’s failing eyes – is uniquely haunting.

The sparse music includes a Bollywood party song at Parima’s colleague’s farewell, Punjabi aunties crooning a folk tune on the metro, Swanand Kirkire’s Maai Teri Yaad post-rape, a sleazy Bhojpuri item number as the missing CCTV tech’s caller tune, and Mohit Chauhan’s Mann Hawa in the end credits, which leaves you with renewed hope.

Final Word

Assi has its flaws, but once again, Anubhav Sinha shows maturity in handling a pressing social issue, sparking vital debates with fresh perspective. While watching, my mind flashed to news of a Koppal court sentencing three men to death for gang-raping an Israeli tourist and murdering two others near Hampi, a crime from March 2025. That’s swift; Nirbhaya’s parents waited eight years. Foreign cases draw international pressure, but we hope police and judiciary match this efficiency for thousands of local victims. The law takes its course, but as a society, we must confront why India sees so many rapes. Only then can we hope of bringing Assi down to shunya.

Video review below.